Investors are often seduced by the dazzling performance of market darlings. The headlines proclaim the “top five best performers” of a given year, implying that outsized returns are simply a matter of identifying the next breakout. In 2021, the ASX was led by Novonix, Cettire, Liontown Resources, AVZ Minerals, and Imugene. Each delivered eye-watering gains in the calendar year, ranging from 300% to more than 650% within the twelve months of the calendar year.

For the casual observer, these names seemed to offer confirmation that chasing momentum was a viable strategy. Yet with the benefit of hindsight, the subsequent decline in their share prices has been equally dramatic. In most cases, investors who entered near the peaks of 2021 have seen the majority of those paper gains evaporate.

The Hype Cycle and the Reality of Fundamentals

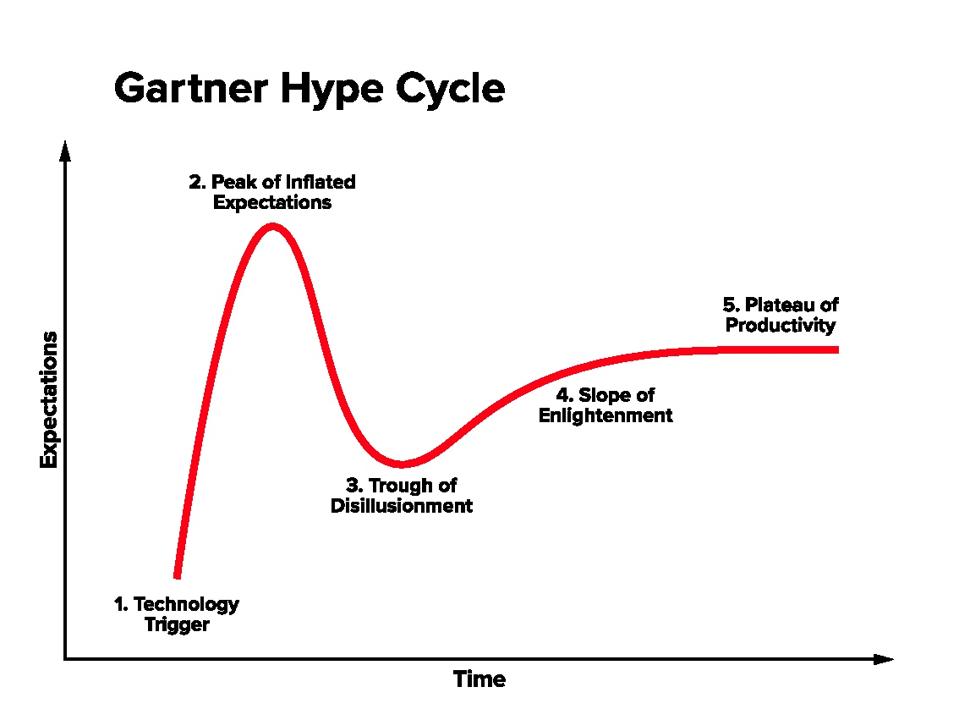

This dynamic reflects a well-documented cycle of exuberance and disappointment. The Gartner Hype Cycle, often used in technology adoption studies, offers a helpful analogy. Early optimism propels valuations to unsustainable levels, yet when expectations collide with operational realities, the “trough of disillusionment” follows.

Companies that lack robust business economics — measured by consistent earnings growth, return on capital above the cost of equity, low debt-to-equity and durable competitive positioning — struggle to sustain inflated valuations. The gap between price and intrinsic value eventually closes, and it usually does so at the expense of late-arriving investors chasing “hot stocks”.

By contrast, the Teaminvest methodology begins with risk mitigation rather than speculation. Our process is designed to filter out what we call Capital Killers, businesses with weak balance sheets, poor earnings growth, or unsustainable economics.

The outcome of such filtering is not a perfect strike rate, as no methodology can eliminate investment risk entirely. There will be holdings that disappoint or periods where share prices decline. However, the essential point is that when our discipline identifies genuine Wealth Winners, the compounding of returns over many years more than offsets the impact of those setbacks.

As Warren Buffett observed, “only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” In markets, that tide is the passage of time and the scrutiny of operating performance.

Evidence in Numbers

A simple exercise illustrates the difference. Imagine placing $5,000 evenly across the top five “trend” stocks of 2021, alongside the same $5,000 invested across all companies that passed Teaminvest’s triage process on 4 February 2022. By the close of 30 September 2025, the “trend” portfolio had collapsed to just $1,179.57, representing a loss of more than 75% of capital. Meanwhile, the Teaminvest portfolio had grown to $8,914.64, a gain of nearly 80% over the same period..

| Portfolio (invested from Feb 2022) | Companies (5 x $1,000 each) | Value by Sept 2025 | Gain/Loss |

| Top 5 performers of 2021 | Novonix, Cettire, Liontown, AVZ, Imugene | $1,179.57 | –$3,820.43 |

| Teaminvest (all passed triage) | The average of all companies that pass Triage | $8,914.64 | +$3,914.64 |

The distinguishing feature of the latter group was not that they captured headlines or delivered extraordinary one-year returns, but that they possessed operating histories marked by stable earnings, solid capital management, and a demonstrable capacity to reinvest at attractive rates of return. These businesses were not insulated from market volatility, yet their underlying economics meant that time worked in their favour.

The Mathematics of Compounding

What the comparison underscores is the fallacy of extrapolating short-term returns into the future. Markets may reward a story for a year or two, but unless the business economics support long-term value creation, those rewards prove fleeting. The speculative investor, in effect, plays a different game from the disciplined investor. One is engaged in momentum arbitrage, hoping that sentiment holds long enough to pass the parcel. The other accepts the slower gratification of business ownership, measuring success not in calendar years but in decades.

The choice between these approaches is not simply philosophical; it is mathematical. Compounding requires both return and duration. High returns over a very short period contribute little to long-term wealth if followed by steep losses. Moderate but consistent returns, sustained and reinvested over time, deliver exponential outcomes. The mathematics of wealth creation favours patience over prediction.

It is tempting to believe that with enough information or intuition, one can identify the next market star. History suggests otherwise. The discipline of filtering, analysing, and valuing companies as businesses — rather than betting on trends — remains the most rational path to preserving and growing capital. Investors should remember that headlines capture moments, but portfolios compound over years.